Carolyn Gage, a leading feminist American playwright interviews Raquel Almazan on the decade long journey of building La Paloma Prisoner Project.

READ THE FULL INTERVIEW: HERE

Interview with Raquel Almazan1/29/2020 Raquel Almazan CG: I’m interviewing the amazing Raquel Almazan, a fellow playwright who also an actress, educator, film director, dance practitioner, and art activist. She has been awarded numerous grants and received numerous awards. And she has participated in writing development workshops with such brilliant artists as David Henry Hwang, Lynn Nottage, Theresa Rebeck, Charles Mee, Edward Albee, Horton Foote, Morgan Jenness, Julie Harris, Naomi Ilizuka, and Carmen Rivera. Some of her plays include La Paloma Prisoner, CAFÉ, La Negra, When I Came Home, La Migra Taco Truck, Dar a Luz, Does that Feel Good to you My Lark? A Doll’s House Adaptation, and Cross//Roads: Re-framing the Immigrant Narrative. From her website: “Raquel was born in Madrid – Spain, is also of Costa Rican descent and has lived most of her life in the U.S. As an interdisciplinary artist she holds an M.F.A. in Playwriting from Columbia University. B.F.A. in Theatre from University of Florida/New World School of the Arts Conservatory. She develops work as a writer, director, actor, dramaturge and is also a Butoh dance practitioner. Almazan is the Artistic Director of La Lucha Arts, producing several of her original works, including Latin is America, a play cycle and lecture-performance, a collection of bi-lingual works in dedication to each Latin American country.” We are talking about her play La Paloma Prisoner, a richly imagined play that is pageant, ritual, crime drama, prison play, and an historical epic that comprises vast sweeps of eras and geography. It’s also a play about mothers and daughters, sisterhood—for better or worse, and goddess archetypes. In other words, it is ambitious and daring and transformative. In Raquel’s words, “This new play centers on a woman nicknamed “La Paloma” who targets men who rape girls. During her incarceration, male rapists throughout Colombia continue to turn up dead, leading the public to believe La Paloma may have magical avenger abilities. With the spread of the beauty pageant obsession in South American prisons, this group of incarcerated women organize “The Parade of Prisoners,” calling on ancient rituals of adorning the warrior. These women’s stories interweave Colombia’s social, political, and spiritual history. With their newfound power, the women redefine beauty, their own humanity, and their identity as labeled criminals. La Paloma begins to revolutionize not only the women’s lives, but prison society and the world beyond its walls.”

CG: This just an incredible play… Where to begin? One of the things I love about it, is the recurring themes of mother-daughter love/hate relationships…This is one of the bones I have to pick with the so-called traditional canon, which is, of course, written by men. People defend it by insisting that it is universal in its themes. To that, I always ask, what about mothers and daughters. Shakespeare is filled with father-son conflict and reconciliation, drama often stoked by out-of-wedlock sons and laws of primogeniture that dictated only the first-born would inherit the estate of the father… But where are the mother-daughter scenes? There are some blink-and-you-miss-it ones in Romeo and Juliet, but that’s pretty much it. So I love how much you treat themes about mothers and daughters in this play. RA: First, I’d like to deeply thank you Carolyn for the wonderful words in describing the play and for framing the play within this context. Immediately I realized that coming in and doing this work was about forming families very quickly, and realizing “I’m the mother” and other times “I’m the daughter, I’m receiving so much right now, and I’m being held.” So I think that was really the impetus to have so many mother-daughter relationships in the piece. And looking at the world outside of this structure of men to be quite honest, that this was a world in which masculine energy wasn’t penetrating, and so there was this extreme focus on feminine divine energy and feminine healing and for me I looked at that through the prism of mother-daughter relationships. Women have these instincts, as mothers, that we are going to protect, that we are going to protect ourselves and our communities, yet we’ve normalized seeing that as a masculine trait. “The love between mother and daughter, the Oro and Diana characters, who are outside of society create their own personal society of righteous crime. To remove themselves from helplessness and poverty they create their own code of violence- of thievery to survive, their code is what serves them. What has been taken from them returns to them by the opportunities of gaining what they need. When your own mother, biological mother, cannot protect you, who becomes your mother, your guide? That’s the big question for me, who is the person who is going to protect you? In oppressive societies, I look at it through the lens of women, who is going to become my mother, who is going to become my protector, and I think that Paloma takes that role. CG: And ritual… La Paloma Prisoner is so filled with allegory, sacred objects, song and dance, I felt that the entire play was a ritual of healing and exorcism. Where did that come from? Are you a witch? RA: Lol… I am absolutely a witch! The play also has many extended dance/ritual sequences that counter balance this violence with healing. Based on Butoh dance and cultural rituals we take back the body as an anonymous figure that is being processed for a jail sentence in the beginning of the play to the journey of the end of the play- where the woman explore their new bodily identities that take form. The body is the conduit of the holy spirit. We need not be separated but to honor the body in space is to join our heart, mind and spirit. In the world of La Paloma Prisoner, the play offers a spiritual communication with those who have died. The play has a series of celestial meetings between the women and their loved ones. The wall that closes the women in also creates a need for us to break into this world, when Paloma becomes a celebrity of vengeance for women around the world, physical walls begin to tumble down. A portal opens. In Colombia, The worshipping of the Guativita Lagoon Goddess by the indigenous Muisca people, involved the beautification of the body, the ritualization of the body, that involves painting the body gold and adorning the body with colorful dress and jewelry. The beautification of the body is also a symbol of health and fertility. I endowed the characters with the agency of honoring their fertility, power and sexual potency that does not need the dependency of men. The ability to call on the spirits with this worship often calls on altering the body and preparing the body for this type of spiritual exchange. The modern use of makeup in the pageant as a mask is used in this exchange today in order to call on the Patron Saint of Prisoners, The Virgin of Mercedes takes place on Sept. 24, every year at the Buen Pastor Jail. The use of song was inspired by the opening song of the pageant when I visited Buen Pastor, the women celebrated 200 years of Colombia’s independence by singing the national anthem. At one of the facilities in South Florida I brought in a piece of fabric, going back to the essentials of theater, that one piece of colorful fabric that turned into all these other literal things, and also expressive things, where you could dance with it in rehearsals. They really were taking to these colors, and they said, “I would like to adorn myself with that, with this feather boa,” and then that became this portal. When we put it on and we did a dance, it was as if they were somewhere else, it was very transportive, and it was just like having that one piece of material that connected them not only to femininity but to identity. The dove Paloma bird is often a symbol of peace and the animal has the ability to spiritually release the dead. Paloma birds honor the dead by leading spirits to their place in the after life. Paloma in the play leads men to their afterlife as a vigilante figure. She also transforms the harm done against her and manifests it into a power. Instead of letting the abuse done against her destroy her, she wields a force to help others, and to end the cycle of violence against women by committing her own violence directly against the abusers. This is a revolutionary concept for women to defend themselves against their abusers in their home, work place and societies at large. She can be seen as an anti- hero because of her use of violence- but that is a question I leave for the audience. The supernatural aspects of her power is also a question for how we view our physical reality. Those who can enter the metaphysical world can have the power to travel in and out of supernatural worlds. I also believe that the dead spirits of women fuel Paloma and aid her power to break barriers out of the jail. Celestial forces transcend the physical world.

CG: Blood. Talk to us about blood. When I look at the classic Western plays in the canon, and especially the epic ones with large casts and huge themes… there is a lot of blood. The heroes litter the stage with bodies. Women’s theatre has always seemed to me to be at a terrific disadvantage because we have not been warriors in the same sense as men, who train to become soldiers and march off to territorial wards. But, of course, we are incredibly warriors in reality… just unsung. In the yin-yang world of patriarchal theatre, we are the bearers of life and men are the destroyers of life. What I love in your play is that your women get to be both. And they don’t just grab the gun in self-defense and off their batterer. These women kill, with intention, with gusto, without remorse, and with absolute premeditation. Where did you find the archetypes for this… and then the courage to put them on the stage? And how are they received? RA: Woman as warriors is an ancient concept that is being revisited in the jail of Bogota. The parade of prisoners – the day before the pageant is an event where the women adorn themselves in a variety of wardrobes, costumes and personas. Some include ancient indigenous dress of the people who inhabited the Colombian region before colonization. There are rules of sacrifice in the world of the play, rules of the ancient world and the roles the modern characters play out in the play- a new cycling. Whether you live in small tribal communities, small towns or a large metropolis, we are all playing roles that make that society function. Being in an all woman’s jail- Paloma refers to it as a kind of freedom where she is surrounded by the worship of feminine dynamics and re- building of women’s community. But the jailers, reporters, solider, father, and men that were part of the women’s past break in and out of the play- that represents the constant forces that play against women around the world. Does female vengeance create a balance in the universe, to counterbalance all the violence and hate created by men? This is a question Paloma battles with. When Paloma thinks there will be a film made about her, it leaves a mark of immortality while she very well knows she could be murdered at any minute. The Greek Gods and myths were scripted, the Kings and Queens of Shakespeare, the historical figures that were wealthy always got their stories recorded and dramatized. But why not the average person who struggles, the ones that are seen as too small and insignificant? Paloma makes herself into a figure that can not be ignored, made historical, given value to, made into a God, so that no one could claim that she suffered and acted in vain. CG: So finally… Can you tell us something about the development history of this play? Have you taken it into a women’s prison and if so, how did that go? And where are you going with it? RA: I was moved twenty years ago when I first stepped into a maximum security facility for women to train as an arts facilitator and was startled, not only because of the stark physical conditions, lack of human contact devised by the system but by the communal history of abuse that the majority of the women shared. I myself being a survivor of domestic violence and sexual assault was immediately connected to the necessity to process and stage narratives that needed to be reclaimed by women in the system. The script has been in development for over ten years, across four countries. Workshop production at The Signature Theatre off-Broadway. (Selected for World Theatre Day: Performing Gender and Violence in Contemporary National and Transnational Contexts Conference in Rome, Italy. Tre Roma University reading) (Women’s Playwrights International Conference- Stockholm, Sweden) (The Lark Play Development Reading, NYC) (Labyrinth Theatre Intensive reading) (Staged Reading at La Mama ETC and INTAR). Critical Breaks Residency directed by Estefania Fadul (Hi-Arts). Attendance in Bogota, Colombia at the (Buen Pastor Prison) for the Annual Celebration and Beauty Pageant. The play and a portion of it’s programming has been accompanied by post-show activities with criminal justice activists, extending audience engagement and citizen action events; including panel discussions, The Impacted women series and tours of the play to facilities. (The Impacted women series) was funded by the Arthur J. Harris Award at Columbia University; an initiative that combines women who have experienced the criminal justice system alongside performers to engage with audiences with the themes of mass incarceration. On June 1st 2017 excerpts of the play were performed at Greenhope Services for Women as well as Queensboro Correctional Facility for Men in New York City; in collaboration with impacted women.

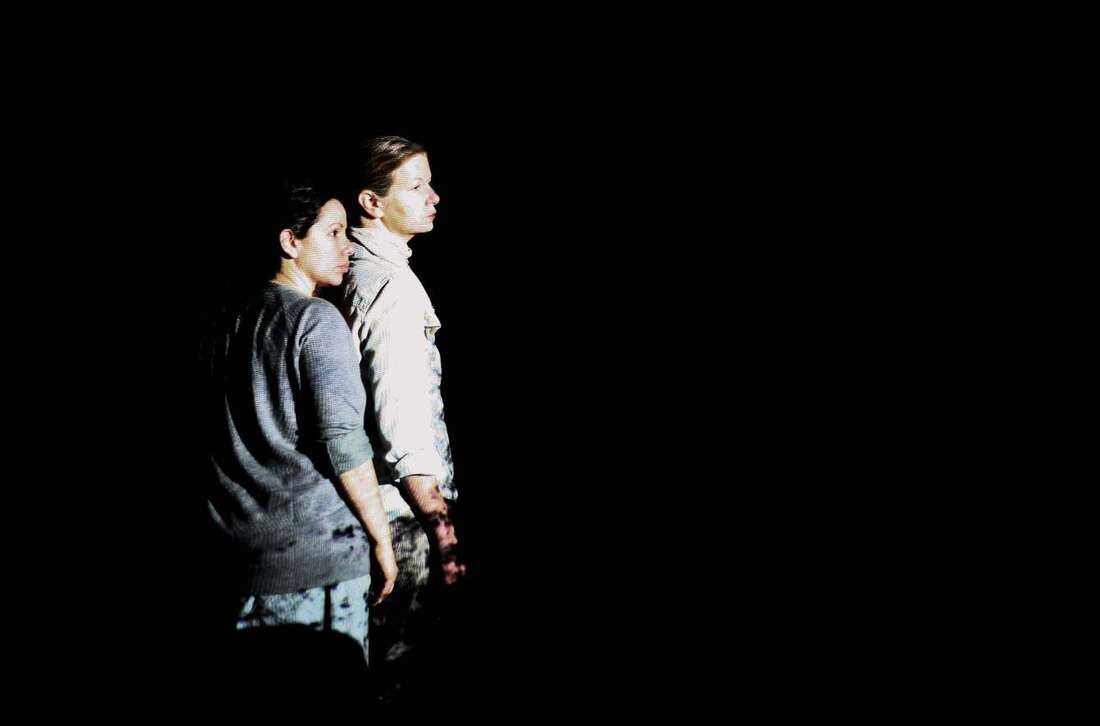

Through a grant from the National Association of Latino Arts and Culture, recently in December of 2019, we were able to perform the play at the Rose M. Singer facility on Rikers Island for a small group of women. There is very little programming for the women at Rikers and our presentation in the gymnasium was the largest event of the year. Since it was a small group of women and our ensemble we were able to have an intimate conversation with them about how the play resonated with them, what they received from the relationships the women formed and their interest in the Colombian mythology. It’s always difficult to walk out of a jail knowing that while the exchange was uplifting and transformative, it is just a portion of what is needed to liberate oppressive conditions and systems. Here is a current description of the larger project and information about the upcoming off-Broadway world premiere: La Paloma Prisoner is programmed as part of the Next Door series with New York Theatre Workshop 2019/2020 Next Door series for a full theatrical run from April 19th – May 9th, 2020, directed by Estefania Fadul. Check it out!About the La Paloma Prisoner Project:La Paloma Prisoner is a theatre project by Raquel Almaƶán about the reclamation of identity by incarcerated and formerly incarcerated women in the prison system. Developed from her longstanding work with incarcerated and impacted communities, the play will have its World Premiere at Next Door @ New York Theatre Workshop in spring 2020, alongside a series of initiatives aimed at raising awareness and inciting action towards the end of global mass incarceration. The project includes programs designed to uplift the voices and narratives of current and formerly incarcerated women-identified folx of color through workshops in prisons, conversation circles, a mini symposium, and panel discussions leading up to the production’s scheduled run at NYTW in April. |